December 02, 2025

Spatial Variability of Soil Physicochemical Properties and Their Implications for Climate-Smart Agriculture in Niger State, Nigeria

1.0 INTRODUCTION

Healthy soils form the backbone of resilient food systems, shaping not only what farmers can grow but also how communities adapt to climate pressures. Yet, across northern Nigeria, decades of continuous cultivation, minimal soil amendment, and advancing climate variability have accelerated nutrient depletion and reduced soil productivity; trends consistently highlighted in regional soil studies and recent nationwide assessments showing declining organic matter and fertility in sandy-loam savanna soils. In response to these challenges, ThriveAgric undertook a comprehensive soil analysis across four major agricultural LGAs in Niger State (Lapai, Paikoro, Bosso, and Chanchaga) to generate localized, evidence-based insights that address a critical gap in soil data for this region.

Previous research highlights that sustainable productivity gains depend on understanding soil physicochemical properties at micro-level scales, as nutrient profiles vary widely even within similar ecological zones. This study aims to illuminate the specific fertility constraints and opportunities in Niger State’s soils, offering practical intelligence for donors, investors, agribusinesses, policymakers, and development partners.

The findings in this study aim to translate scientific soil diagnostics into actionable pathways that strengthen fertility management, boost yields, and build climate-resilient agricultural systems for the smallholder farmers who anchor local economies.

2.0 METHOD

A total of ten composite soil samples were systematically collected from agricultural fields across the four study LGAs (Lapai, Paikoro , Bosso, and Chanchaga) at depths commonly used for agronomic assessments. Standard soil laboratory procedures were used to characterize each sample. Particle size distribution (sand, silt, and clay) was determined using the hydrometer method based on USDA classification standards, enabling accurate textural classification. Soil pH was measured in both distilled water and 0.01M CaCl₂ solution using a calibrated digital pH meter. Organic carbon (OC) was analysed using the Walkley–Black wet oxidation method, while total nitrogen (TN) was quantified via the Kjeldahl digestion and distillation technique.

Available phosphorus (AP) was extracted using the Bray-1 method and measured colorimetrically with a UV-visible spectrophotometer. Exchangeable bases (Ca, Mg, K, and Na) were extracted with 1N ammonium acetate (pH 7.0) and analysed using an Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (AAS), with potassium and sodium further validated using a flame photometer. Exchangeable acidity (H⁺+Al³⁺) was determined by titration after extraction with 1N KCl. Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC) was subsequently computed from the summation of exchangeable cations and acidity. These methods, widely adopted in soil fertility diagnostics, provide a comprehensive assessment of soil nutrient status and land-use suitability.

3.0 RESULTS

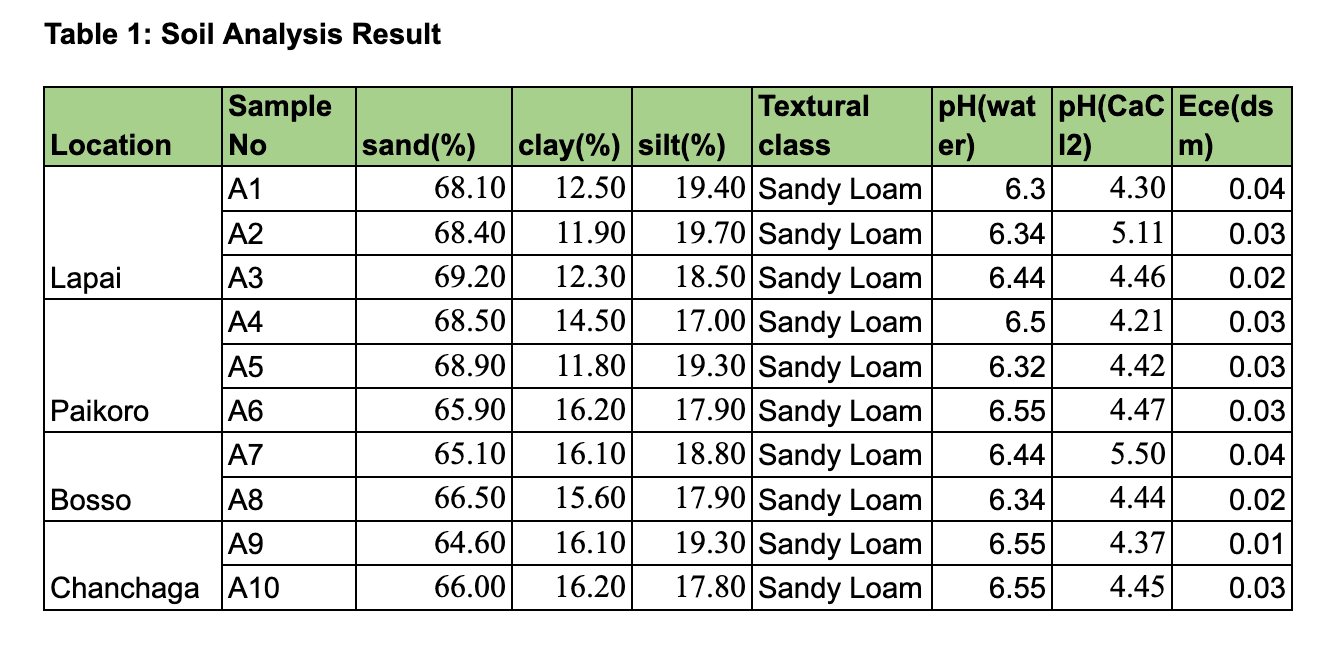

3.1. Soil Texture: Dominance of Sandy Loam Across All LGAs

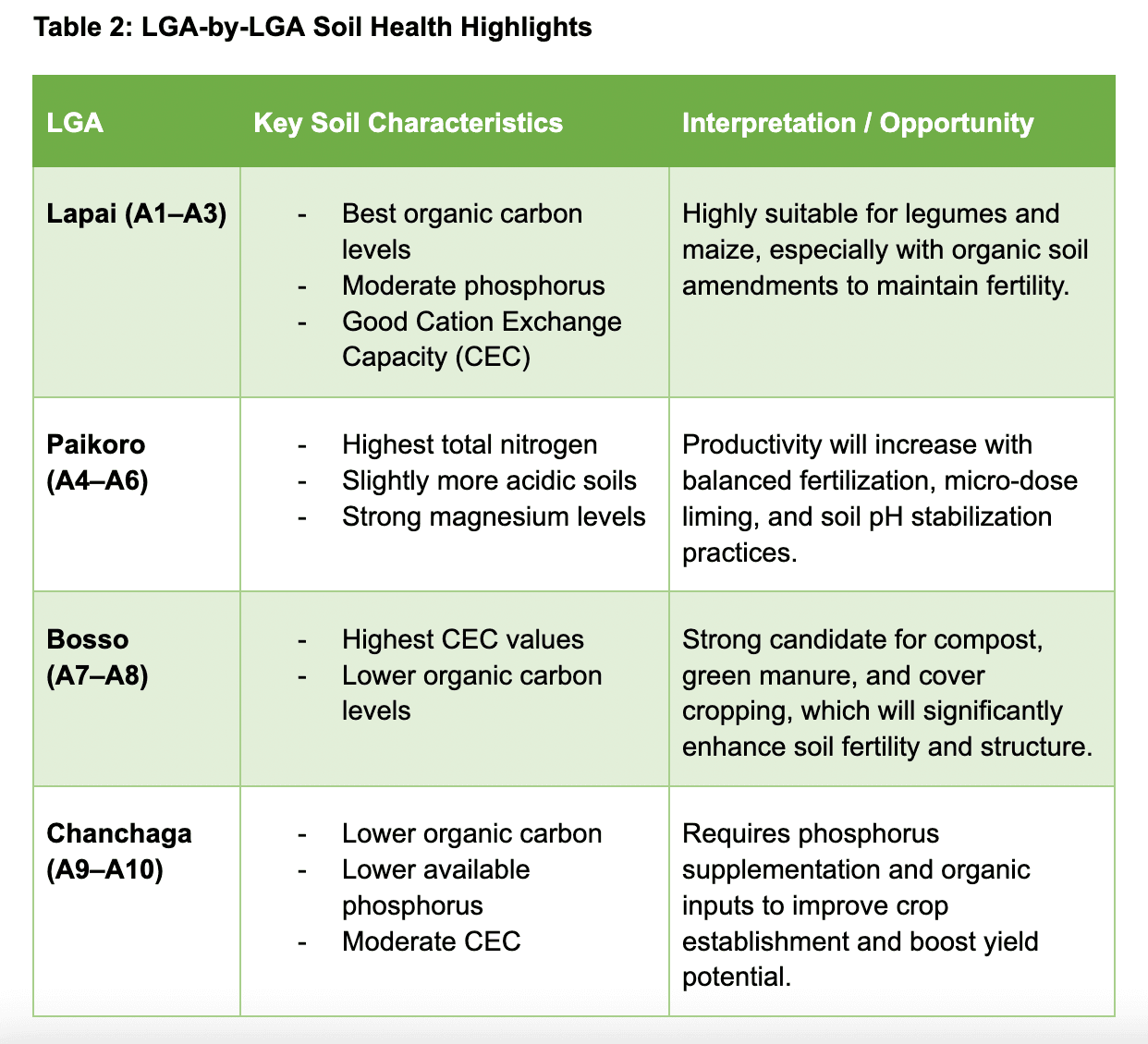

Across all four LGAs, the soil samples consistently exhibited a sandy loam texture—a soil type widely recognized for its excellent drainage yet relatively low nutrient and moisture retention. Subtle variations were observed: samples from Lapai and Paikoro contained slightly higher clay proportions, reaching up to 16.2%, indicating a marginally better ability to hold water and support root development. In contrast, soils from Bosso and Chanchaga displayed similar sandy loam characteristics with moderate silt content, reinforcing a uniform textural profile across the study area. The predominance of sandy loam suggests that these soils are inherently responsive to organic amendments, mulching, manure incorporation, and other climate-smart soil management strategies designed to enhance water-holding capacity and buffer against nutrient loss. Strengthening soil structure through increased organic matter will therefore be essential for improving crop productivity and sustaining long-term soil health in these communities..

3.2. Soil Acidity: Slightly Acidic Conditions Suitable for Most Crops

The soil pH (measured in water) across all samples ranged between 6.30 and 6.55, reflecting a slightly acidic environment that remains highly suitable for a wide range of crops, including cereals, legumes, root crops, and vegetables. Paikoro samples showed marginally higher acidity in CaCl₂ measurements (dropping to about 4.21) indicating greater sensitivity to nutrient availability shifts, while soils from Lapai demonstrated more stable pH values. Overall, the acidity levels fall within the optimal range for nutrient uptake and biological activity, suggesting that large-scale liming is unnecessary. However, periodic pH monitoring is recommended to mitigate progressive acidification, especially in areas with intensive cultivation or fertilizer use.

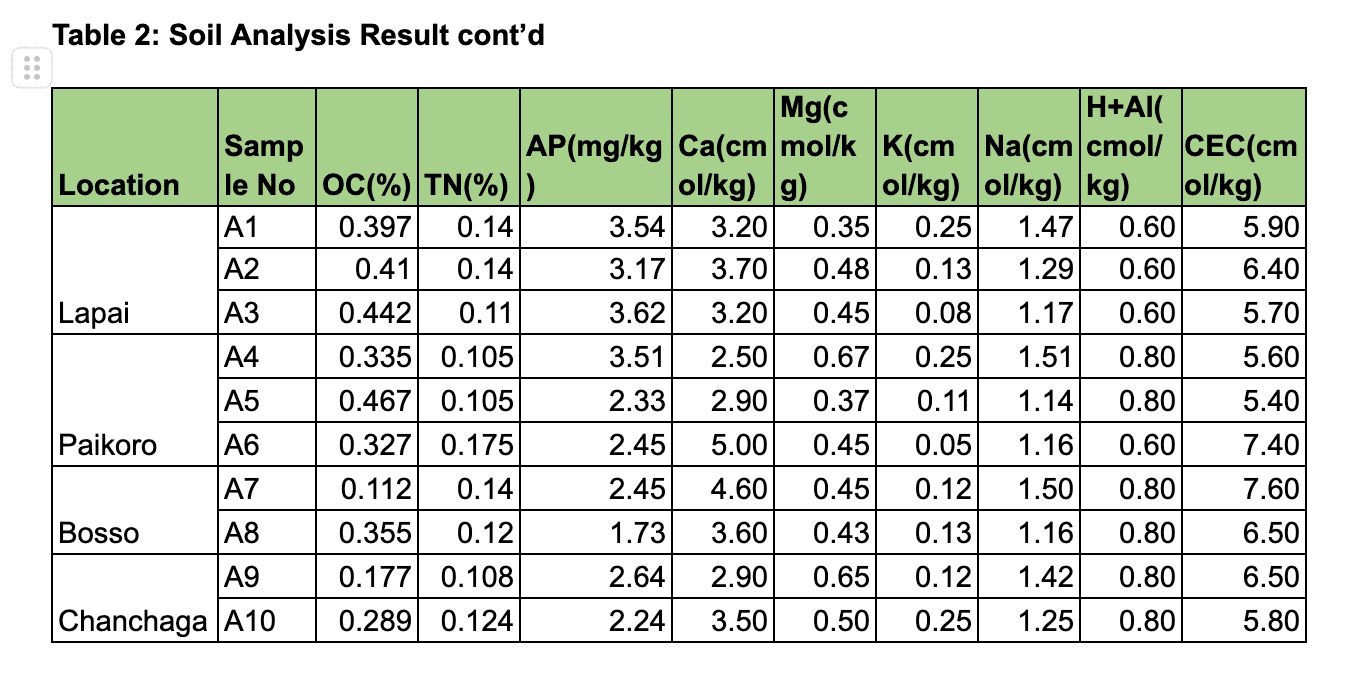

3.3. Organic Carbon and Nitrogen: Low but Improving Potential

Organic carbon levels across the samples ranged from 0.112% to 0.467%, indicating generally low organic matter content and limited inherent soil fertility. Total nitrogen followed a similar pattern, remaining within low fertility ranges (0.105–0.175%). Lapai soils displayed comparatively higher organic carbon levels, while Paikoro recorded the highest nitrogen value, suggesting slightly better nutrient cycling potential in these areas. In contrast, Bosso soils exhibited some of the lowest OC readings, pointing to faster organic matter depletion and reduced soil resilience. Overall, the findings highlight a clear need to enrich soils with organic amendments such as compost, manure, cover crops, and biochar to improve nutrient availability, structure, and long-term productivity.

3.4. Available Phosphorus (AP): Moderately Low Levels

Available phosphorus (AP) levels ranged from 1.73 to 3.62 mg/kg, reflecting moderately low fertility conditions that may limit root development, early crop establishment, and overall yield potential. Lapai soils recorded the highest AP values, suggesting comparatively better nutrient availability, while Bosso and Paikoro showed moderate levels. Chanchaga exhibited some of the lowest phosphorus readings, indicating a greater risk of early-season nutrient stress for crops. These findings show the need for targeted phosphorus supplementation particularly for maize, rice, soybean, and root crops that demand higher P levels for optimal performance.

3.5. Exchangeable Bases & CEC: Moderate Fertility With Improvement Potential

Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC) ranged from 5.40–7.60 cmol/kg, reflecting a moderate nutrient-holding capacity typical of sandy loam soils. Bosso (A7–A8) recorded the highest CEC values (up to 7.60), indicating comparatively better nutrient retention. Lapai soils showed stable moderate CEC levels between 5.7–6.4, while Chanchaga soils exhibited balanced but slightly lower values. Exchangeable calcium and magnesium were generally moderate across locations, though potassium levels remained consistently low in all LGAs. This highlights the need for potassium-rich fertilizers (such as MOP or high-K NPK blends) and organic amendments to enhance soil CEC and overall fertility.

4.0 Discussion: What This Means for Farmers and Development Actors

Niger State’s soil health profile reveals a powerful opportunity and global research backs us. While the sandy-loam soils across Lapai, Paikoro, Bosso, and Chanchaga offer good structure for cultivation, their low organic matter and nutrient content mean they won’t reach full potential without smart, sustained intervention. This is precisely the insight echoed by CGIAR, which warns that up to 65% of Africa’s soils are degraded limiting the effectiveness of fertilizers unless soil health is improved first.

Major development initiatives likewise emphasize the importance of soil restoration. The AGRA Soil Values Programme, for example, co-designs soil fertility solutions with communities in West Africa (including northern Nigeria) to blend organic nutrient sources with inorganic inputs for sustainable yield gains. Similarly, the IFDC’s Soil Values initiative shows that integrated soil fertility management (ISFM) can raise productivity while building resilience across Sahelian landscapes.

In line with these insights, our data suggest that with deliberate investment (such as organic amendments, tailored K- and P-based fertilizers, and climate-smart practices) smallholder farmers in Niger State could realistically boost crop yields by 25–40% within a few seasons. This isn’t just a hopeful projection. Similar strategies under ISFM in the Ethiopian Highlands delivered substantial yield improvements across crops, according to Cambridge University-led research.

Our analysis highlights a powerful opportunity that cannot be ignored. This potential calls for bold action. Private-sector input suppliers can expand tailored fertilizer blends and soil-specific solutions. Government extension systems can pivot toward evidence-based, farmer-friendly advisory services. Development partners and investors can scale climate-smart agriculture financing that builds long-term soil resilience.

As food insecurity deepens across northern Nigeria, Niger State holds a strategic advantage. Its soils are not worn out, they are undernourished yet highly responsive, offering a unique window to boost productivity and strengthen climate adaptation. With targeted investment, Niger State can turn its soil health profile into a competitive edge and its farmers into drivers of sustainable growth and food security.

5.0 Conclusion

This soil assessment demonstrates that Niger State possesses a strong foundation for agricultural transformation. The soils across Lapai, Paikoro, Bosso, and Chanchaga are workable, moderately fertile, and highly responsive to improvement; conditions that position the state for rapid gains in productivity if supported with strategic interventions. However, the consistently low organic carbon, modest nitrogen levels, and limited phosphorus highlight a clear need for sustainable soil enrichment practices.

These findings directly align with the pillars of climate-smart agriculture, where improved nutrient management, organic matter restoration, and water-efficient practices strengthen both productivity and resilience. Prioritizing CSA practices such as (composting, cover cropping, agroforestry, and biochar integration), this can significantly boost yields while enhancing the soil’s capacity to withstand climate variability.

Crucially, the low organic carbon levels present an untapped opportunity for carbon farming. Increasing soil carbon stocks through regenerative practices not only improves fertility but also enables farmers and partners to participate in emerging carbon markets turning better soil management into an economic asset.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). (2017). The future of food and agriculture: Trends and challenges. FAO. https://doi.org/10.4060/i6583e

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). (2021). Status of the world’s soil resources: Main report. FAO.

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). (2022). FAOSTAT statistical database. FAO.

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD), UNICEF, World Food Programme (WFP), & World Health Organization (WHO). (2023). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023. United Nations. https://doi.org/10.4060/cc3017en

International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). (2019). Fostering sustainable soil fertility management. IFAD.

International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD). (2022). Rural development report: Transforming food systems for rural prosperity. IFAD.

Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA). (2020). Feeding Africa’s soils: Fertilizer and soil health systems report. AGRA.

Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA). (2021). Africa agriculture status report: Building resilient food systems. AGRA.

CGIAR Research Program on Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS). (2019). Climate-smart agriculture: A global evidence review. CGIAR.

CGIAR. (2020). Soil health and crop productivity: Key research insights. CGIAR.

World Food Programme (WFP). (2021). Building climate-resilient food systems. WFP.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). (2019). Climate change and land: An IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes. IPCC.

Lal, R. (2015). Restoring soil quality to mitigate soil degradation. Sustainability, 7(5), 5875–5895. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7055875

Sanchez, P. A., & Swaminathan, M. S. (2005). Cutting world hunger in half. Science, 307(5708), 357–359. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1109057

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). (2020). Preventing the next pandemic: Zoonotic diseases and how to break the chain of transmission. UNEP.

Related Content

May 15 2024

ThriveAgric Makes Top 20 on FT's Fastest Growing Companies List

Dec 02 2025